As a college staff who had studied in South Korea but working in the U.S. now, I get to see and experience differences in the higher education system in the U.S. and South Korea. Recent researches, however, have pointed out that the higher education system in the U.S. and South Korea has commonalities in the sense that the system is stratified. This is alarming especially for college faculty and staff because it means that students’ personal backgrounds like race, socio-economic status, and gender play a huge role from admission to post-graduation economic mobility.

With four pieces of research and an interview with one researcher, this article aims to shed a light on the societal issues that stem from stratified higher education in the U.S. and South Korea and share what can be done to fix the issue.

First, Council for Opportunity in Education issued New Equity Indicators this year and found that the college admission system is stratified. According to the New Equity Indicators report, the student’s family’s socio-economic status impacts not only the college access but also the student’s completion rate. For example, the number of high school graduates in 2013 who are from high socio-economic status and are admitted from selective 4-year colleges is eight times higher than the number of students who have poor financial resources.

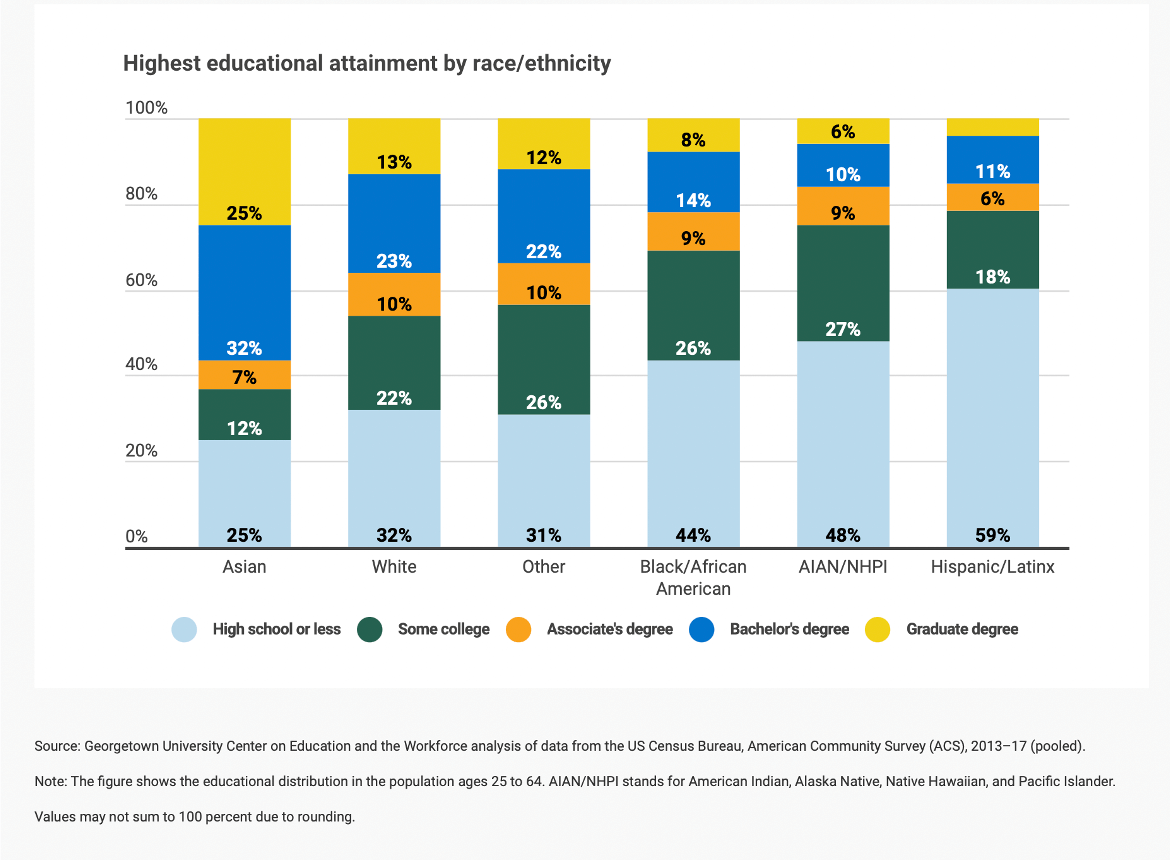

◆Highest educational attainment by race/ethnicity ©Council for Opportunity in Education

Even after students get into college, the completion rate differs based on students’ race, ethnicity, and socio-economic status (SES). What is more, another research found that the value of the college degree plays differently based on these factors; race and SES. Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and Institute of Higher Education Policy formed the Postsecondary Value Commission (PVC) and published a 115-pages long report that contains 2 years of the research result regarding the value of postsecondary education.

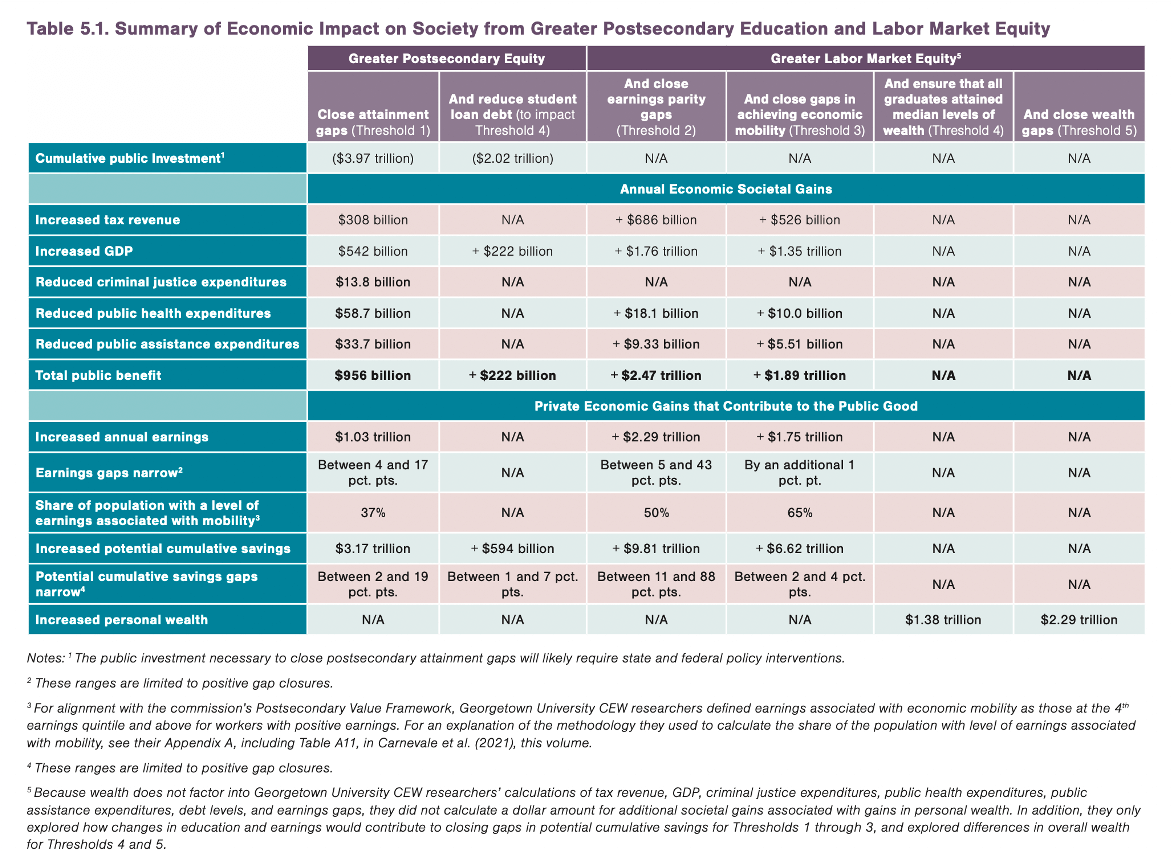

◆Summary of Economic Impact on Society from Greater Postsecondary Education and Labor Market Equity © Postsecondary Value Commission

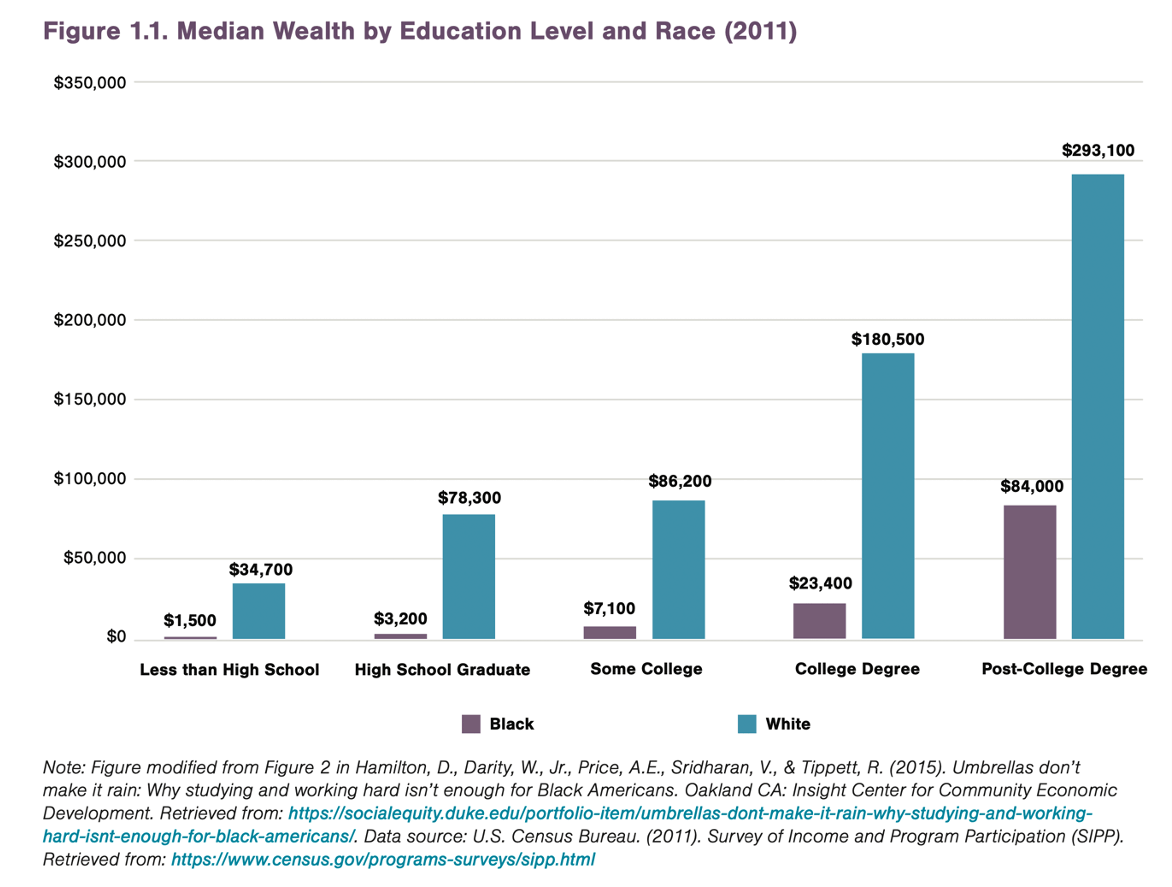

PVC found that the postsecondary degree does help students to earn more, regardless of their race. The problem is Black students who obtained post-college degrees have less wealth than White high school graduates who did not go to college.

The main culprit of this gap comes from the debt. In 2019, the average amount of tuition loan that four-year college graduates owe is around $28,950. But when we look at this number closely, White students borrowed around $34,717, whereas Black students borrowed almost double-approximately $62,824. Thus, Black students and students from lower socioeconomic status could find the college degree less valuable to move up the social ladder.

◆Median Wealth by Education Level and Race ©Postsecondary Value Commission

Now, let’s look at the higher education system in South Korea. Recent research on postsecondary education in South Korea by Sangwoo Lee, a Ph.D. candidate at the Department of Education at the University of Cambridge, echoes the aforementioned researches in a way that the higher education system in South Korea is stratified as well.

In his research, Lee found two things; first, higher education in South Korea is less effective for female students in terms of social mobility. Second, the most selective and prestigious universities in South Korea play the role of “glass floor,” rather than “social ladder.”

Lee elaborated on the concept of the glass floor via email; “The ‘glass floor’ protects less able but better-off children from falling down the social ladder as they become adults. For instance, those from affluent backgrounds are more likely to find decent (but unpaid) internship opportunities based mainly upon their parental social networks, which in turn would allow them to find a better job in the labor market upon graduation.” According to Lee’s another research, “in South Korea, there exists a socioeconomic gap in the earnings of female graduates who attended the same type of higher education (either 2-year or 4-year college) and studied the same discipline subject.”

In Lee’s perspective, one of the plausible explanations that higher education systems in the U.S. and South Korea are stratified is “their emphasis on the standardized test” like SAT in the U.S. and Soo-Neung in South Korea when it comes to college admissions. He added that “many people, particularly in South Korea, tend to believe that the standardized test is the justest and fair system, determining whom we accept to higher education institutions.” Lee acknowledged that more and more universities in the U.S. are dropping SAT/ACT score requirements but “the longer-term change would be necessary to reduce the educational and economic inequalities in society.”

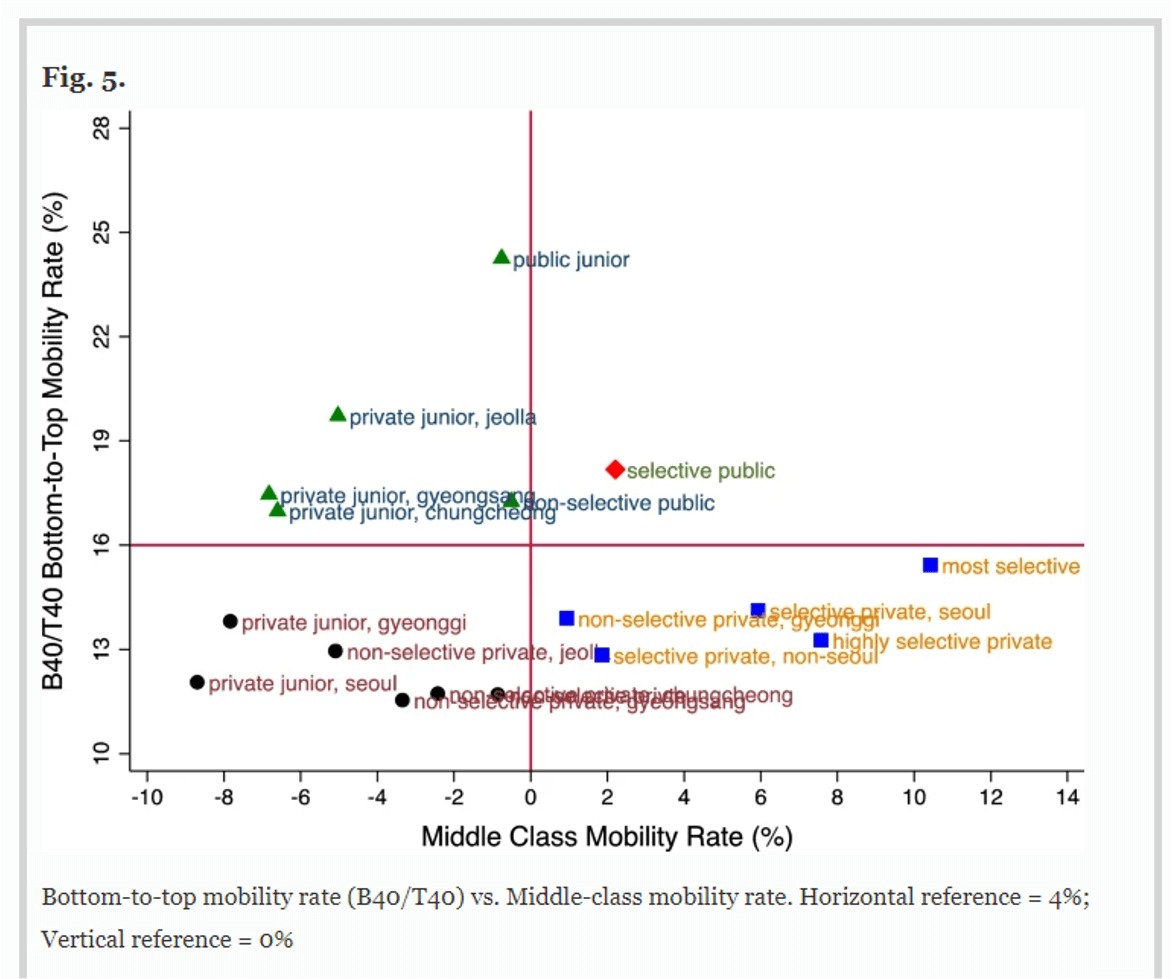

Virtually all researchers of the papers agree that the problem of colleges and universities being stratified is a societal issue. The simulation created by Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce shows that the societal cost caused by the education attainment gap is about $956 billion dollars per year. Sangwoo Lee also supports this claim; “The stratified higher education system is highly more likely to reproduce socio-economic inequalities existing in Korean society, given that richer students dominate the places at the most selective universities. Many statistics have indeed shown that roughly 70 percent of students at elite colleges in Korea are from the top income quintile.”

◆Bottom-to-top mobility rate vs. Middle-class mobility rate ©Sangwoo Lee

Then the question arises, how can we make the higher education system more flexible where all students can have equitable access, support, and be equipped for a just society, regardless of their race/ethnicity/gender/socioeconomic status? Lee believes that “diversifying the student body within colleges would be the first mission for universities, particularly for the most selective ones.”

In order to do that, colleges and universities should have “fairer, data-driven, and transparent admission policies to enhance the equality of opportunity or to diversify the student body, particularly in the most selective universities.” Lee proposes “the contextualized admission.” The contextualized admission indicates that “universities assess an applicant’s prior attainment and potential in the context of their individual circumstances based on a wider range of information and data. This system allows schools to assess applicants given the individual situations they went through, including but not limited to their educational, geo-demographic, and socioeconomic background data.” “It would cost a lot; however, still, this would be the first step in the right direction,” Lee added.

To better support less advantaged students in terms of economic and social mobility, colleges and universities should team up with the government or society. For example, the gender pay gap is still an issue in the U.S. and South Korea. In the same vein, “wage differentials go well beyond those driven purely by degree attainment or institution attended, and richer students, on average, still earn more than their counterparts from poorer backgrounds even when they study the same discipline subject at the same university,” Lee said. Therefore, Lee suggests “greater and broader support for those from poorer backgrounds, while they are at universities, would be necessary.”

On a final note, Michael Sandel, a political philosophy professor at Harvard University who recently published his new book “The Tyranny of Merit: What’s Become of the Common Good?” said “It’s a mistake for us to think that if we’re worried about inequality and if we’re worried about mobility, the answer is higher education. It’s only an answer for a tiny fraction of our students. We need to pursue other responses to inequality because telling people go get a college degree, that’s not a good enough solution.”

As many experts and researchers have noted, colleges and universities should start with analyzing admission data and completion rates, etc to solve the issue. The next step will be collaborating with related entities to better support disadvantaged students. Only when the higher education system can provide fairer opportunities and programs to students, all college graduates will be able to experience the true value of postsecondary education. That’s when the expectation of students, parents, and society for higher education to be a vehicle for social mobility and a just society will be met.

References

- Postsecondary Value Commission

- Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce

- New Equity Indicators Report Reveals Systemic Barriers to College Access and Success for Low-income and Non-traditional Students by Council for Opportunity in Education

- Lee, S. (2021). A Social Ladder or a Glass Floor? The Role of Higher Education in Intergenerational Social Mobility. Higher Education Policy

- Admission by lottery: A proposal to reimagine college acceptance written by Andy Uhler and Erika Soderstrom

Writer’s bio:

Hanna Lee

Hanna is currently a SEVIS and International Services Coordinator at SUNY Oswego. She received her B.A. in Mass Communication and Journalism from SungKyunKwan University and Ed.M. in Higher Education Administration from University at Buffalo. Hanna also runs the website (sevissavvy.com) where she shares her expertise in F-1 and J-1 visa regulations and updates in Chinese, English and Korean for international students.